With the current global pandemic, many are concerned about what's to come and feeling a little stressed.

As we navigate through this situation, our health understandably comes into focus. Unfortunately, this uncertainty can lead to more stress, which can impact your health, including your gut. But how does the gut play a role in stress?

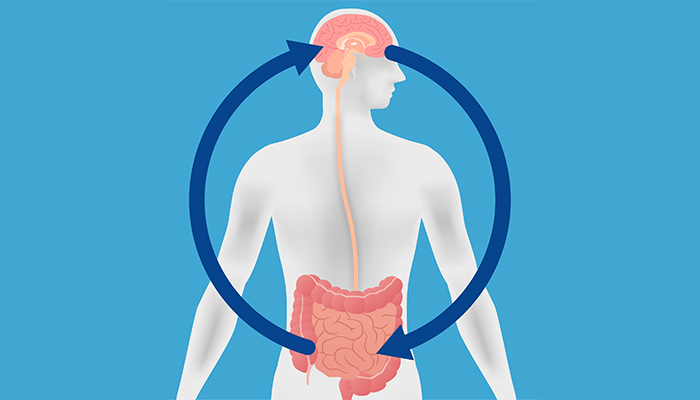

The gut-brain connection: what happens to your gut when you are stressed?

When you are under stress your body tries to support you by releasing stress hormones. These hormones flood your body to help you get ready to respond to the “threat”. This results in many physical changes like sweating, a pounding heart and rapid breathing. A lot of people also feel stress in their stomach or bowels. Feelings of nausea, a loss of appetite or an urgent need for the toilet can be experienced by people who are stressed. But did you know that stress and the associated hormones may also impact your gut microbiome?

Research has shown that even short exposures to stress can shift the types and numbers of bacteria found in the gut1.

This might help explain why scientists have discovered that people with stress-associated conditions such as depression have gut microbiomes (the community of bacteria living in your gut) that are different from healthy people2,3.

How smart is your gut? Read the blog.

Can you manage your stress through your gut microbiome?

Did you know that your gut communicates with your brain? They talk to each other in multiple ways including through your nervous system. The main nerve that connects the gut and brain is called the vagus nerve4. Messages run in both directions along this nerve, however, most of the communication travels from the gut to the brain4. The vagus nerve can be activated by serotonin, a chemical messenger also known as a neurotransmitter4,5. Serotonin is linked with changes in mood, bowel function and general wellbeing6. It can be produced by special cells in our gut when stimulated by the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) butyrate and propionate5,6. SCFAs are produced by beneficial gut bacteria that feed on dietary fibre (called prebiotics7,8). In fact, the research found that taking a prebiotic supplement (B-GOS) was associated with reduced stress hormone levels in a group of healthy adults9.

You can also support your gut microbiome’s ability to produce SCFAs naturally by eating a variety of prebiotics – such as resistant starch – found in plant-based foods.

Scientists have discovered that some of our gut bacteria can produce another mood-associated neurotransmitter called GABA. While they don’t yet fully understand the role that GABA produced in our gut influences our mood, we do know that diet seems to be important. The Mediterranean diet (a dietary pattern generally high in prebiotics), has been associated with reducing both depressive symptoms and the risk of developing depression10,11. Also, some foods naturally contain GABA, including fermented foods, bean sprouts, spinach and barley12. So diets rich in prebiotics appear to play an important role in supporting a healthy gut microbiome in a way that may also support our mental health.

Want to know more about prebiotics? Learn more.

Practical strategies to help manage stress

The global pandemic has certainly changed the way most of us live our lives. But this gives us a chance to start some healthy habits – habits that could also help manage the stress associated with these uncertain times.

Gut-to-brain strategies – fuel your microbiome through healthy eating:

- Fill your plate with plenty of prebiotic, plant-based foods such as wholegrains, vegetables, legumes, nuts and seeds!

- Try going Mediterranean one or two days a week and try foods such as baked fish with roasted vegetables.

- Try going meat-free one or two days a week and enjoy large bowls of salad with legumes or roasted capsicum stuffed with zucchini and quinoa.

Brain-to-gut strategies – Find time in your day to focus on you. With many people having a reduced daily commute, why not fill this “extra” time with:

- Exercise – find an activity you enjoy or get on YouTube and follow along to a Zumba, Pilates, or circuit class. You could also make a home gym or go for a run.

- Do something that brings you joy – mediation, gardening, artwork, playing or listening to music, reading or soaking in the tub…quiet the mind and find something that tunes out the world.

- Connect in the real world. Close down the social media apps and reach out to your family and friends, either over the phone or in-person (while practising safe social distancing).

This microbiome test is not intended to be used to diagnose or treat medical conditions. A full disclaimer is available here

References

Hantsoo, L., et al.,.

F160. Cortisol Response to Acute Stress is Associated With Differential Abundance of Taxa in Human Gut Microbiome. .

Biological Psychiatry, 2018. 83(9, Supplement): p. S300-S301.

Anglin, R., et al., .

The Gut Microbiome in Patients with Anxiety, Depression and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. .

Neuropsychopharmacology, 2014. 39: p. S289-S289.

Winter, G., R. Hart, and C. Sharpley, .

Gut microbiome and depression: what we know and what we need to know..

Reviews in the Neurosciences, 2018. 29(6): p. 629-643.

Breit, S., et al., .

Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders..

Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2018. 9: p. 44.

Mohajeri, M.H., et al., .

Relationship between the gut microbiome and brain function. .

Nutrition Reviews, 2018. 76(7): p. 481-496.

O’Mahony, S.M., et al., .

Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. .

Behavioural Brain Research, 2015. 277: p. 32-48.

Koh, A., et al.,.

From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. .

Cell, 2016. 165(6): p. 1332-1345.

Singh, R.K., et al., .

Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. .

J Transl Med, 2017. 15(1): p. 73.

Schmidt, K., et al.,.

Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers. .

Psychopharmacology, 2015. 232(10): p. 1793-1801.

Sánchez-Villegas, A., et al., .

Mediterranean dietary pattern and depression: the PREDIMED randomized trial. .

BMC medicine, 2013. 11: p. 208-208.

Opie, R. S., O'Neil, A., Jacka, F. N., Pizzinga, J., & Itsiopoulos, C. .

A modified Mediterranean dietary intervention for adults with major depression: Dietary protocol and feasibility data from the SMILES trial. .

Nutritional Neuroscience, 21(7), 487–501. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1312841

Mazzoli R, Pessione E.,.

The Neuro-endocrinological Role of Microbial Glutamate and GABA Signaling.(gamma-aminobutyric acid)(Report)..

Front Microbiol. 2016;7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01934.